10 Dec The Diversity of Philippine Music Cultures

by Felipe Mendoza de Leon*

“At the rate our people are bombarded with all sorts of Western pop and commercial music through radio, television, jukeboxes, record players, and movies – the day may not be too far away when we shall have committed our own native music to the grave; harshly forgotten, abandoned, its beauty laid to waste by an unknowing generation whose only fault is not having been given the chance to cultivate a love of it…” – Felipe Padilla de Leon

Philippine music is rich beyond compare. Most Filipinos, however, do not know this wealth, victims as they are of a broadcast media that propagate Western, particularly American entertainment music, day in and day out. If ever music written by Filipinos is given a chance to be heard, it is ninety percent of the cheap pop variety copied or adapted from foreign hits.

Our young people hear almost nothing of the creative music of the people of Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The vast output of our serious composers, who ironically are mostly Manila-based, is also unknown to them.

There is a pressing need to bring Philippine music closer to our people: strong identification of our own music is one vital factor in bringing our people together or unifying the nation.

Exposing Filipinos to their own musical traditions is properly the task of the government, our music educators, musicologists, community leaders, concerned media practitioners, performing groups, pro-Filipino radio and television stations and recording companies, heritage centers and libraries, and cultural organizations all over the country.

A survey of the whole range of authentic Filipino musical expression reveals at least eight major types according to cultural sources and influences:

Traditional Filipino Music

I. Music of Indigenous Southeast Asian Filipinos: Harmony with the Creative Forces of Nature

This is the music of the indigenous, strongly animist, though nominally Christian, non-Muslim peoples of the highlands of the Cordillera (ex. Ifugao, Kalinga, Isneg, Ibaloi, Kankanay, Bontoc), Mindoro (ex. Hanunoo, Buhid, Alangan), Mindanao (ex. T’boli, Mansaka, Tiruray, Bagobo, Manobo, Subanun), and Palawan (ex. Batak, Tagbanwa). Sometimes these people are called lumad. Their music generically may be called by the same name. An example of lumad music is that of the Kalinga tongngali (nose flute) or T’boli hegelong (lute).

Our indigenous peoples are the closest to nature. Life to them is an indivisible whole. Art, myth, ritual, work, and activities of everyday life are all integrated into one. Spirit and matter, God and nature, the visible and invisible worlds are not a dichotomy but interpenetrate in many ways. Of all Filipino subcultures, indigenous art is the most integrated with everyday life, multifunctional and participatory.

To the lumad everything is alive: rocks, rivers, the wind, fire and air, though to lesser degree, are permeated by the same vital energy that animates biological life.

Creative activity, for the indigenous peoples, is highly extemporaneous and not cultivated as a special gift by select individuals. Oneness with the creative process is a strength of our indigenous peoples and the culture puts emphasis on the creative process rather than on the finished product, making conception and performance simultaneous activities. Lumads can actively interface with the spirit or dream world, the source of their inexhaustible creative energy. Listening to this inner voice or to the Muse within is something we can learn from them.

The music of our indigenous peoples traditionally has the widest repertoire of sounds in the Philippines, perhaps reflecting the myriad forms and enormous biodiversity in their environment. The uniqueness of indigenous music has attracted the proponents of new or experimental music in the West, which is currently fascinated in exploring the entire universe of aural phenomena.

Indigenous music is also the most communal among Philippine musical traditions. Many instruments are often played by three or more people in an interactive, reciprocal, and interlocking fashion, highly indicative of social cooperation, togetherness, and an egalitarian ethos, particularly in the distribution of and access to resources. Musical form is open-ended to provide maximum opportunity for creative communal interaction or participation. Music is very much a part of everyday life and serves many uses and functions.

The unity of opposites, representing the twin cosmic forces holding the universe together – man and woman, forceful and tender, change and permanence, positive and negative – is a core principle among Filipino indigenous peoples. For instance, the hegalong, a two-stringed boat lute of the T’boli of South Cotabato in Mindanao, is an instrument that clearly shows our indigenous peoples’ recognition of the cosmic unity of opposites with its two strings representing change (melody string) and continuity (drone string, playing one note repeatedly).

II. Music of the Moros or Muslim Filipino Cultures: The Courtly Elegance of Islamic Unity

Islamized Filipinos of Mindanao, Palawan, and Sulu, namely the Magindanaw, Maranaw, Tausug, Sama, Badjaw, Yakan, Sangil, Iranun, Jama Mapun, Palawani, Molbog, and so on. Their music may collectively be referred to as Moro music (ex. kulintang music).

Most urban Filipinos are aware of the so-called OPM (Original Pilipino Music), but very few among them know much about the true OPM that continues to be created in the regions. This music is of the highest artistic and technical excellence, such as the music of our Muslim brethren in Mindanao and Sulu. In fact, two outstanding practitioners of Moro music, Samaon Sulaiman of Maguindanao and Uwang Ahadas of Basilan, have already been awarded by the government the highest artistic recognition in the Philippines, the National Living Treasures Award or Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan (which is equal to the National Artist Award).

Muslim Filipinos are among the most creative in the arts. Their religion cultivates a mystical surrender to God’s will. The music of Muslim Filipinos in Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan, blends West Asian mysticism with indigenous Southeast Asian animism.

The vocables and nature sounds of this indigenous music become parts of a seamless rhythmic and melodic web, achieving a sense of flow that is at once majestic and serene.

III. Music of the Lowland Folk Villages: The Way of the Fiesta

The music of the so-called Hispanized lowland Christian, and village peoples of Luzon, Visayas, Mindoro, and Palawan.

Their culture is essentially Southeast Asian, fused with a strong animistic core, though with elements of Latin culture (Mexican, Italian or Hispanic).

The lowland folk are composed mostly of farmers, fishermen, artisans, vendors and traders, and common folk. They have a deep faith in God, whom they serve with utmost devotion. Their key celebration is the fiesta, which revolves around the Sto. Niño, Virgin Mary, Jesus Christ or a patron saint.

The devotional orientation of the lowland folk is a valuable resource for creative yet painstaking and repetitive tasks that require great patience like weaving, embroidery, carving, and metalwork. Their music is often referred to as folk music (ex. pasyon, balitaw, daigon).

Some notable examples of Filipino folk music are: Putungan_, a Marinduque traditional ritual for welcoming important guests; Pamulinawen, a favorite Ilocano song in polka form about a hardhearted woman’s deafness to a lover’s supplications: an Ilonggo-Kiniray-a song medley; and Rosas Pandan, a Cebuano balitaw which celebrates the beauty and charm of a village maiden.

Though belonging to the same subculture, we may observe carefully the intriguing contrasts between the expressive forms of the Ilocano and the Visayan, as manifested in their folk music and dances. Whereas the Ilocanos like their music notes close to each other, Visayan music notes are quite far apart. While Ilocanos love closed, inward movement, the Visayans cherish open, outward movement, as seen in the hand and arm gestures of the dances. Given a dance space, the Ilocanos hardly move away from a center, while the Visayans move around very freely. The Ilocanos’ way of peeling fruits is usually directed towards the body, while the Visayan way is directed away from the body. These opposing styles could be indicative of the contrasting temperament and values of the Ilocanos and the Visayan – the Ilocanos being more reserved while the Visayans more exuberant. Historian Teodoro Agoncillo astutely noted that while Ilocanos are gifted towards survival, Visayans have a penchance for celebrations.

Filipino Popular Melodies

IV. Music of Popular Sentiments: The Sanctity of the Home

This is the music of lowland Christian Filipinos living in town centers or poblacions.

The beginning of what we may consider Western type of music in the Philippines began in lowland Christian town centers, probably around the late 18th century. Instead of being extemporaneous and oral, music creation is now done on paper by an individual author whose name appears on manuscripts or printed music sheets. But with the oral tradition still a strong influence in society, what is written on these musical scores is not sacrosanct, and may be modified by another musician during the performance to allow for individual creative expression. The music may be individually authored but community opinion matters.

Although not to the same degree as that which later developed in the composed music of academically-trained Filipino composers in the late 19th and early twentieth century, the typical European concept of melody functioning within a rational, linear, finite tonal-harmonic framework clearly emerges in this subculture. To be sure the harmony is quite simple and diatonic. The intro and closing portions, which are rather brief, are not given much importance and there is hardly any tension generated in progressing towards a highpoint. The melody is not driven to achieve a single, all-consuming goal. That is, there is no dramatic build-up towards the climax, which is modest or inconspicuous.

Typical examples of this are Constancio de Guzman’s Tangi Kong Pag-ibig and Babalik Ka Rin (both danzas) or Santiago Suarez’ Bakya Mo Neneng (balitaw) and Dungawin Mo Hirang (danza), where the supposedly climactic second to the last note of their melodies hardly creates any tension and quite unsatisfying to musicians used to the powerful climaxes of 19th century Romantic music. Nowadays singers tend to raise this note and prolong it to heighten its dramatic impact and call attention to the singer’s vocal and technical skills.

What the musical features of these songs indicate is that the musician is not fully separate from the society in which he lives. As an individual artist he can provide social entertainment to his community, yet shares much of its sentiments. He likes to be appreciated for his work but at the same time has the same concerns and is dependent on co-existence with his neighbours. He is not a professional or specialist hired for the purpose, though he may be given a token gift or compensation for his efforts. He himself belongs to the group he performs but not in the same degree that an indigenous or folk musician is part of his community.

Thus, he does not simply perform for his listeners but performs with them, expressing their common feelings through the music that they all enjoy. A performer does not stand before them to simply impress but to articulate for them the music in their hearts. Thus, the performance will include very little of technical display and calling attention to the performer’s musical prowess, unlike in the subculture of the concert hall where virtuosity or technical brilliance can become an end in itself.

The culture of the poblacion, which is not quite rural yet not quite urban, is the wellspring of this cultural heritage. At present, the poblacion dweller is the dominant majority in this country. Thus, his culture may be considered the popular culture of the Philippines.

The popular culture of the Filipinos is not the same as the popular (the mass or “pop”) culture of the United States. The symbols, images and forms of Filipino popular culture are enduring while those of the latter are fleeting and ephemeral.

The music of this subculture, often called light music, is the authentic popular music of the Filipinos, and not the one brought to us by American mass or “pop” culture, as is commonly thought. “Pop” music is a big influence among the middle to upper class urban youth in our more industrialized towns and cities.

But it is not strong enough to dislodge Filipino popular music from its pre-eminence in our social life, as attested to by the enduring legacy of songs composed in the 1940s or earlier yet continue to appeal to the popular sensibility, whether old or young, such as Constancio de Guzman’s Maalaala Mo Kaya and Pamaypay ng Maynila, Mike Velarde’s Dahil sa Iyo and Ikaw, Santiago Suarez’ Bakya Mo Neneng and Sa Libis ng Nayon, Josefino Cenizal’s Hindi Kita Malimot, and Juan Silos’ Bingwit ng Pag-ibig.

“Pop” music is apparently popular because of media hype. But its appeal is shallow and cannot compete with the lasting popularity of these songs.

If they are not as popular as before, it is simply because the fresh vitality of newer songs that incorporate some contemporary rhythmic and harmonic elements but with practically the same melodic style and emotional content have attracted Filipinos after the 1950s, like Matudnila, Usahay, Saan Ka Man Naroroon, Gaano Kita Kamahal, Dahil Sa Isang Bulaklak, and Lagi Kitang Naaalala.

Most of these songs are of a sentimental nature since they emanate from a culture centered on social connections. Filipino popular culture retains the devotional orientation of folk culture but, being more secular, the object of devotion is now the family and one’s social network of friends and acquaintances and sanctity of the home.

Though still the focus of community unity, the center of devotion is no longer the patron saint, Sto, Nino, Virgin Mary or Jesus Christ. The family becomes the bedrock of existence and the home is the haven of rest, symbolized by the Filipino ancestral house. Sentiments that foster family togetherness and values that ensure family members will be have respectable positions in the community (mabuting puwesto), stability, and advantageous social and political connections are cultivated.

The bearers of this culture possess an irresistible urge to connect to people and explore, understand, establish or affirm relationships, always seeking the ties that bind. We find in them the romantic Filipino. The one who falls in love with love, the one who likes to cry in the movies. This is the Filipino who is fond of watching telenovelas, like Marimar, Rosalinda, Monica Brava, Jumong or Jewel in the Palace.

It is no wonder then that the most popular type of song in this culture are love songs, as embodied in the danza or harana. The danza, not the kundiman, is the love song par excellence of Filipino popular or light music. It is in moderately slow to slow duple meter, with a rhythmic pattern akin to that of the tango or habanera, minus the tango’s physical bravura and sexual languor.

In social gatherings that foster friendships, camaraderie, fellowships and community unity, however, the tango as a ballroom dance together with the waltz, slow drag, swing, cha cha and other social rituals such as the rigodon de honor and cotillion continue to function as an important part of this subculture.

Music for Listening

V. Music of the Concert Hall: The Autonomy of Music

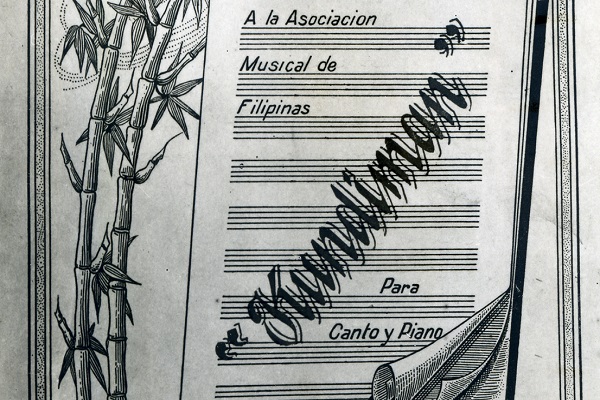

This is the music of highly individualized composers who are formally trained in Western-style conservatories or colleges of music. This music is also known as “serious or classical music” (ex. Nicanor Abelardo’s Mutya ng Pasig, Francisco Santiago’s Taga-ilog Symphony, Lucresia Kasilag’s Divertissement for Piano and Orchestra).

Most Westernized Filipinos listen to concert music and are thus the most individualistic. Self-reliance, self-promotion, and specialization are highly encouraged, resulting in a weaker sense of community and greater sense of privacy. Social interactions become more competitive and adversarial. Relationships become more impersonal, formal, and merely functional rather than holistic. Communication tends to be verbal and explicit, particularly through writing. Reflective, critical, analytic, linear, scientific, and dualistic thinking (left brain thinking) are highly valued.

Most intellectual Filipinos usually come from the academe. And it is the academe that largely sustains a Filipino culture of reflection or one devoted to the cultivation of the intellect. Higher institutions of learning, such as the University of Sto. Tomas, the University of the Philippines, University of San Agustin, St. Scholastica’s College, Sta. Isabel College and others, train composers and musicians dedicated to the creation and performance of what is known as serious, concert or classical music. Music becomes autonomous, independent of other human concerns or aspects of everyday life, and is valued almost solely for its aesthetic qualities.

Concert music is appreciated for its own sake. Music is no longer part of everyday life, like putting a baby to sleep, work, healing or rituals. It is cultivated as a separate human activity, has its own space (concert hall, opera house, etc.) and is performed in its own time (for active, concentrated listening). Listening to music becomes a reflective, contemplative or intellectual activity.

Largely influenced by the European and American ideology of art for art’s sake, serious music places much emphasis on the marking of linear time and the idea of formal development through the organization of tonality, harmony, rhythm, and melody. Serious or classical music is either under the light category or heavy category.

VI. Music for Mass Entertainment: The Consumerist Lifestyle

This is the music of highly urbanized and industrialized towns and cities. It is produced mainly for mass entertainment and it is what we know as “pop” music. When we talk of the music industry in this country, it refers mainly to this type of music (ex. Ryan Cayabyab’s Kay Ganda ng Ating Musika, George Canseco’s Ngayon at Kailanman, and many others called OPM by their producers).

Pop music needs no introduction. It was inculcated in us by the American music industry through radio, television, movies, and other electronic media. Its most energetic adherents are the highly urbanized youth.

Though called OPM, Philippine popular music is mostly American in form and style and only its words are in Filipino. It is the least indigenized or “Filipinized” of all the foreign-influenced music traditions in the country. It is more accurate to call it music with OPL (Original Pilipino Lyrics). Notable exceptions are the works of songwriters who have, to a certain degree, Filipinized the pop music idiom, like Freddie Aguilar’s Anak, Florante’s Handog, Gary Granada’s Salamat Musika, and Louie Ocampo’s Ikaw.

Pop music’s origins are traced from the North American culture of entertainment and cultivation of instant pleasures. This music is variously called pop, mass media, entertainment and commercial music. Pop culture is the culture of the 3Ms – Mickey Mouse, McDonald and Madonna.

Pop music is also a culture of celebrities and superstars, its hype leading to the adulation of pop icons and the proliferation of clones.

Music for Social Awareness and Human Dignity

VII. Music of Social Concern and Cultural Freedom: A Force for Social Transformation

This is the music for social criticism and cultural liberation and is variously termed alternative, protest, progressive or people’s music. (ex. Joey Ayala’s Wala Nang Tao Sa Santa Filomena and Heber Bartolome’s Tagulaylay).

The music of this genre has always been in the process of experimentation, change, and growth, since the American period when socialistic ideas began to emerge in Filipino society. It is being actively shaped today by socially committed poet-musicians who are consciously using songs as a force for social liberation, advocacy of social justice, and in the struggle for human rights. It harnesses music as an instrument of social criticism and change, taking up the issues of injustice and oppression, neocolonialism, cultural erosion due to globalization, plight of indigenous peoples, and other social causes.

Music is used as an instrument for social criticism and change, and a vehicle of proposals for more humane attitudes and values, an equitable social order, cultural creativity and diversity, sustainable development, a heightened ecological awareness, and alternative ideas and lifestyles.

Some of the well-known artists who have creatively contributed to this tradition are Asin, Patatag, Inang Laya, Heber Bartolome, Joey Ayala, Grace Nono, Kontragapi, Pinikpikan, Buklod, and recently, the Makiling Ensemble.

Nicanor Abelardo was one of the earliest musicians to compose music for social criticism in the song Kenkoy, with words by Romualdo Ramos. Kenkoy was composed in the 1930s to satirize the first generation of Filipinos who began aping American ways in superficial and ridiculous ways, often at the expense of their self-respect and dignity. It was inspired by Kenkoy, a whacky character created by Tony Velasquez in 1926, who is a colorful embodiment of “veneration without understanding.”

VIII. Music for National Identity: Being Filipino

These are songs that celebrate or depict our struggles, hopes, and aspirations toward a Filipino identity and sense of nationhood.

The Filipino struggle for freedom identity and dignity has a long and continuous history since the 16th century when Spanish colonization began. The Filipinos were the very first Asian peoples to wage and win a war in 1898 against Western colonialism in Asia. We were also the first Constitutional Republic in Asia. A commitment to one’s country and pride in being Filipino, though only discernible among a minority (thus, a subculture), is as alive today as it was in the past, and this devotion has always been well-served by the musical expressions of the nation, particularly the kundiman, a song of devotion to a selfless and noble cause. It is the kundiman that has always embodied the Filipinos’ intense and lofty patriotism, as in the songs Bayan Ko, Jocelynang Baliwag, and Sariling Bayan.

The kundiman is a tenderly lyrical song in moderately slow triple meter with melodic phrases often ending in quarter and half note values. It is mainly a song of selfless devotion to a loved one, the motherland, a spiritual figure, an infant, a lofty cause or an object of compassion.

All of these Filipino music cultures are not only alive and contemporaneous; they are distinct from each other in terms of concept, form, and style. Each represents a way of life that is uniquely Filipino and is expressive of a subculture’s experiences. Understanding these music cultures enables us to understand ourselves better.

We may divide our music cultures into two groups, the first three types of expressions belong to one group and the last four types to another, with the third type straddling the two groups. Though possessing unique characteristics, those musical expressions grouped together have many things in common.

Extemporaneous creation

One shared feature of the first group is the extemporaneous way of creating music – the music is created and performed at the same time. There is no time gap between conception and realization, as when a Yakan creates-performs music in the kulintang (similar to the extemporaneous nature of the poetic joust in Balagtasan).

This is entirely different from the way music is made in the second group, where a musician first writes or records his thoughts on paper and only later does a performer reproduce it in sound, as in writing and performing Ryan Cayabyab’s Limang Dipang Tao.

Thus, the emphasis on the first group is on the creative process while that on the second group is the finished product.

Another feature of the first group is the multi-functional character of the music, which accompanies (or is indispensable in) many activities and events, like putting a baby to sleep, courtship, prayer, debate, protest, merrymaking, and a host of other rituals and celebrations.

In the other group, music has ceased to function in many aspects of everyday life. In the extreme, it has become dispensable, decorative, merely for entertainment, or worse, nothing but a commodity, like many examples of what we call “pop” music.

Also worth mentioning is the collective character of music making in the first group and the individualistic character in the second.

Clearly, our musical traditions, all of them contemporary, can tell us many things about ourselves. Indeed, beginning the study of Philippine music cultures is the beginning of a fuller and deeper understanding of the Filipino.

* FELIPE M. DE LEON, JR. was Chairman of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) and a Professor of Art Studies at the University of the Philippines where he teaches humanities, aesthetics, music theory and Philippine art and culture.

* FELIPE M. DE LEON, JR. was Chairman of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) and a Professor of Art Studies at the University of the Philippines where he teaches humanities, aesthetics, music theory and Philippine art and culture.

He was Commissioner and Head of the Subcommission for the Arts of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the Chairman of its National Committee for Music from 2004-07. He was also Chairman of the Gawad Sa Manlilikha ng Bayan (National Living Treasures Awards) from 1993-2007. He was a Commissioner of UNESCO Philippines (1999-2002) and Chairman of its Committee on Culture (2002).

He was also Chairman of the NCCA’s Committee on Intangible Heritage and Vice-President of the International Music Council (UNESCO), Chairman of the Division of Humanities, National Research Council of the Philippines, Chairman of the Kilusang Kayumanggi sa Ikasusulong ng Kultura (Brown Movement for Cultural Advancement) and Musical Director of Kasarinlan Philippine Music Ensemble.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.